This post is modified and updated from one that appeared on The Planetary Society Blog a month ago.

It’s a rare delight to sink my teeth into a new data set. Last month, ISRO released the first year’s worth of mission data from all of the spacecraft’s instruments, from their Mars arrival up to September 17, 2015. In this post I’ll show you some highlights of the Mars Colour Camera (MCC) data set, then go into more detail about how you can access the data and some of the things I learned about the data set while I was playing with it.

MCC is different from most recent Mars cameras in that it has a very wide field of view, designed so that it is capable of imaging all of Mars’ disk when the spacecraft is near the apoapsis of its highly elliptical orbit. It doesn’t take crisp high-resolution views of Mars; instead, MCC’s value lies in its ability to capture beautifully colored, regional views of the planet that can serve as context images for other missions’ more detailed but much more narrowly focused pictures. Its detector is 2048 pixels square, so its images have plenty of pixels for print publication. For instance, here is a lovely view of a hemisphere of Mars that contains many past and future landing sites:

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

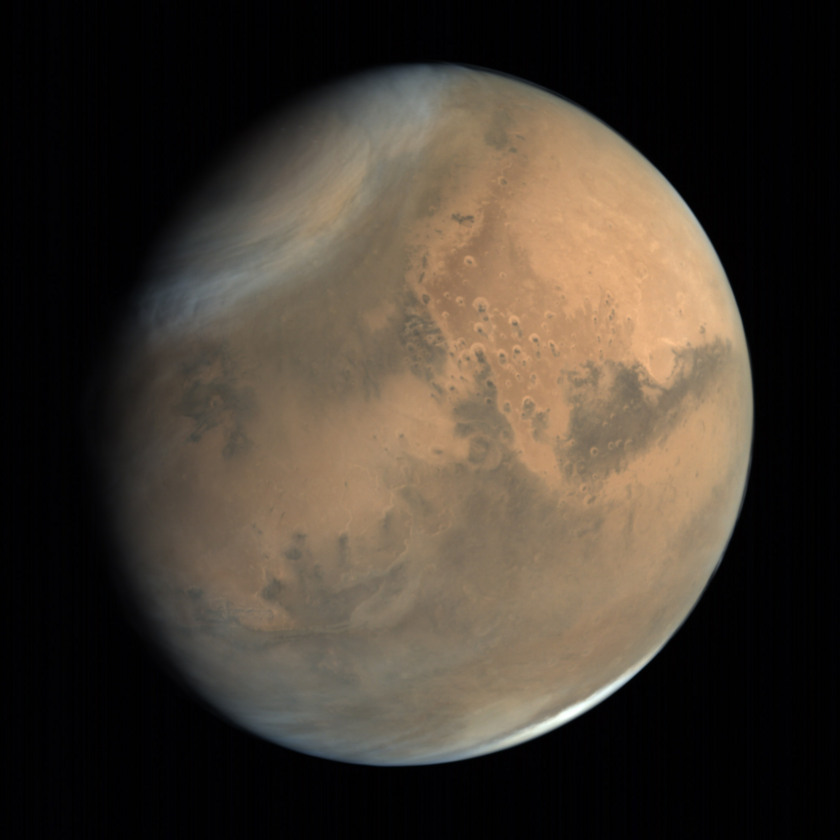

Global view of Mars from MOM: Chryse and Acidalia Planitiae and Kasei, Mawrth, Tiu, and Ares Valles

This global view of Mars contains the landing sites of Viking 1, Mars Pathfinder, Opportunity, and Schiaparelli, as well as the future landing site of the ExoMars rover. It was taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on October 1, 2014, from an altitude of 76,247 kilometers.

Before I write anything else in this blog post, I want to deliver a message to the Mars Orbiter Mission team:

Your full-globe images of Mars are amazing and unique. Please consider shooting more at any phase angle, not just fully-lit ones. No spacecraft has ever captured beautiful, high-resolution images of Mars at a crescent phase. You can. Please shoot more global views at all possible phases that your spacecraft may see: crescent, half-full, gibbous, or full. Such images would be published in books for decades to come.

So now let’s get to the good stuff. First: here is every full-globe image that MCC took, all of them from October, 2014. A remark in the documentation for the data set suggests that they stopped shooting global views after that because they only take full-globe images when they see a nearly fully-lit Mars at apoapsis. Several of these images have been released before, but processed in a way to make them garish and strangely colored. I found that it wasn’t at all hard to produce more realistically colored views from MCC.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

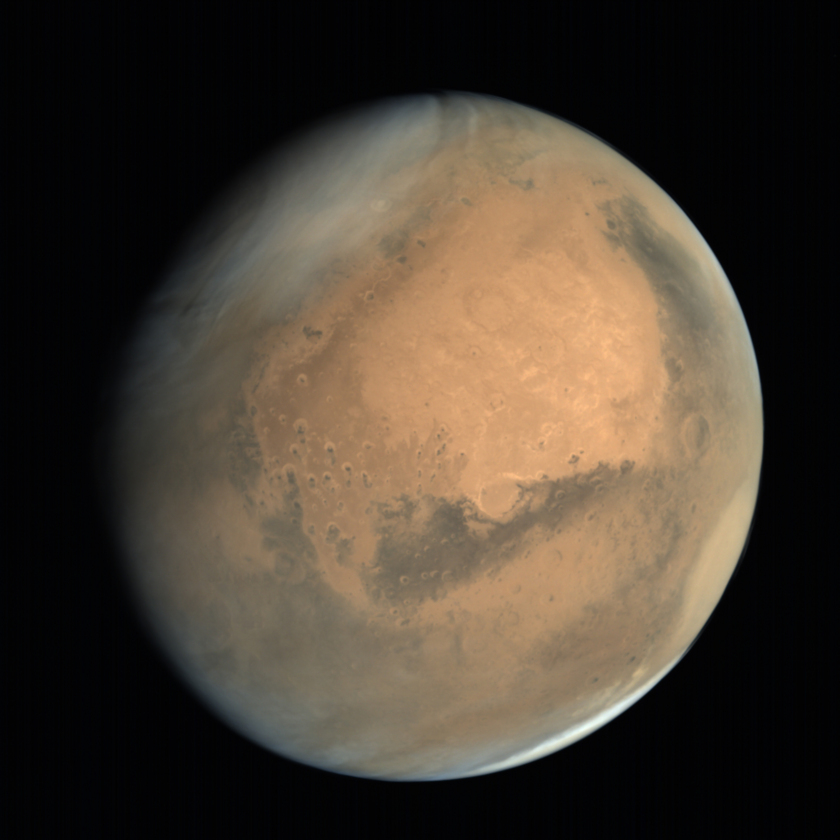

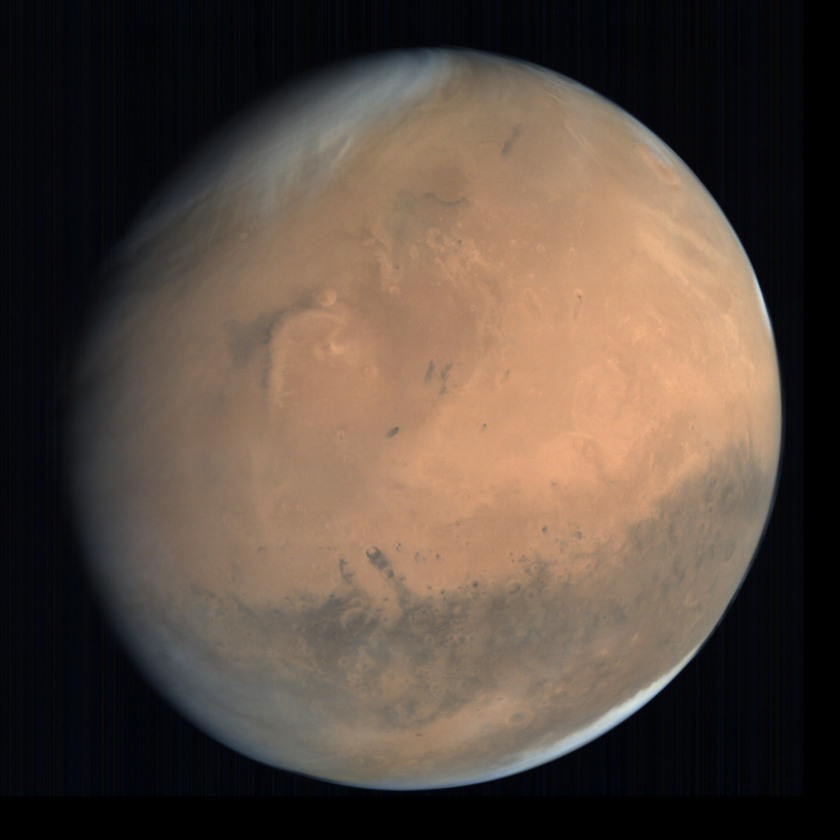

Global view of Mars from MOM: Meridiani Planum

Mars Orbiter Mission caught this global view of Mars soon after arriving in orbit, on September 28, 2014, from an altitude of 74582 kilometers.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

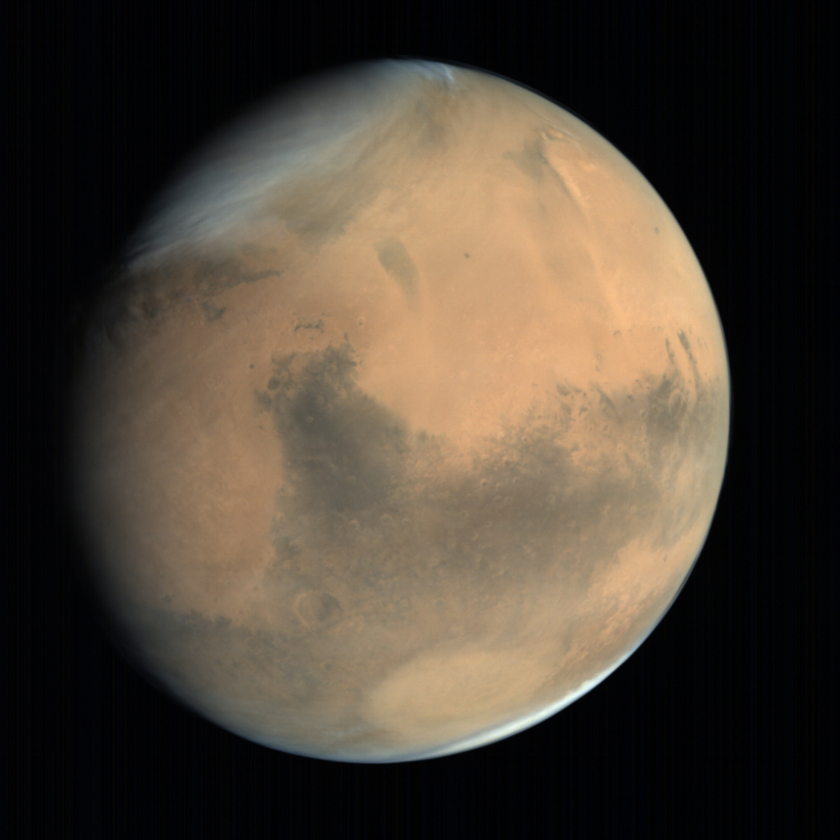

Global view of Mars from MOM: Syrtis Major and Hellas #1

Mars Orbiter Mission captured this photo on October 4, 2014, from an altitude of 72,935 kilometers.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

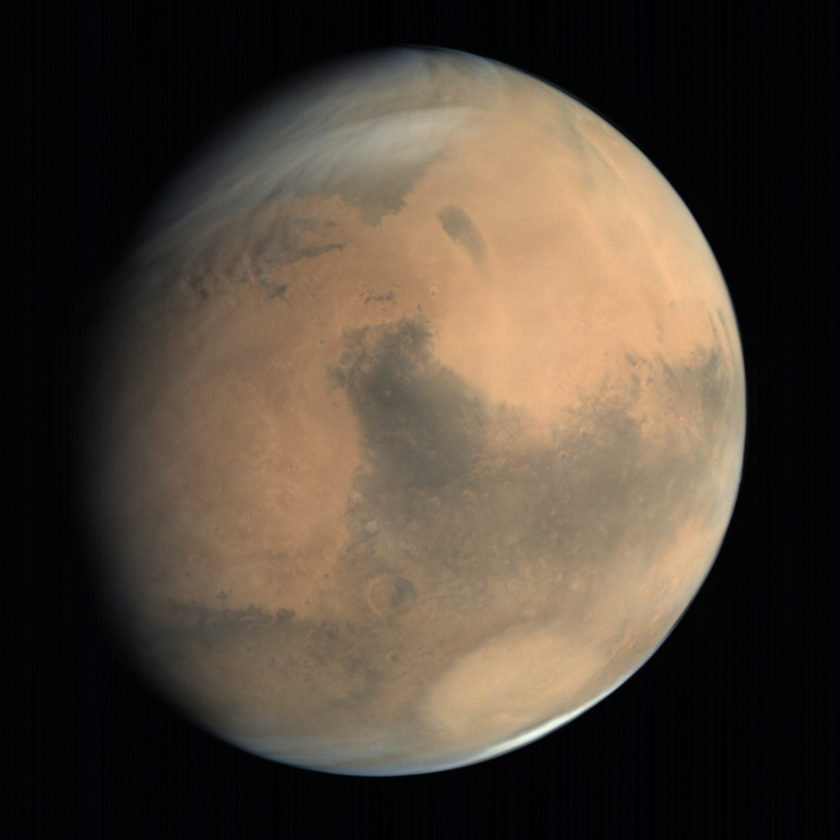

Global view of Mars from MOM: Syrtis Major and Hellas #2

Mars Orbiter Mission took this photo on October 7, 2016 from an altitude of 70,325 kilometers.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Global view of Mars from MOM: Elysium Planitia and Gale Crater

This view of Mars includes the landing sites of Viking 2, Beagle 2, Spirit, and Curiosity, and the future landing site of InSight. Mars Orbiter Mission took this photo from an altitude of 66,552 kilometers on September 30, 2014.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

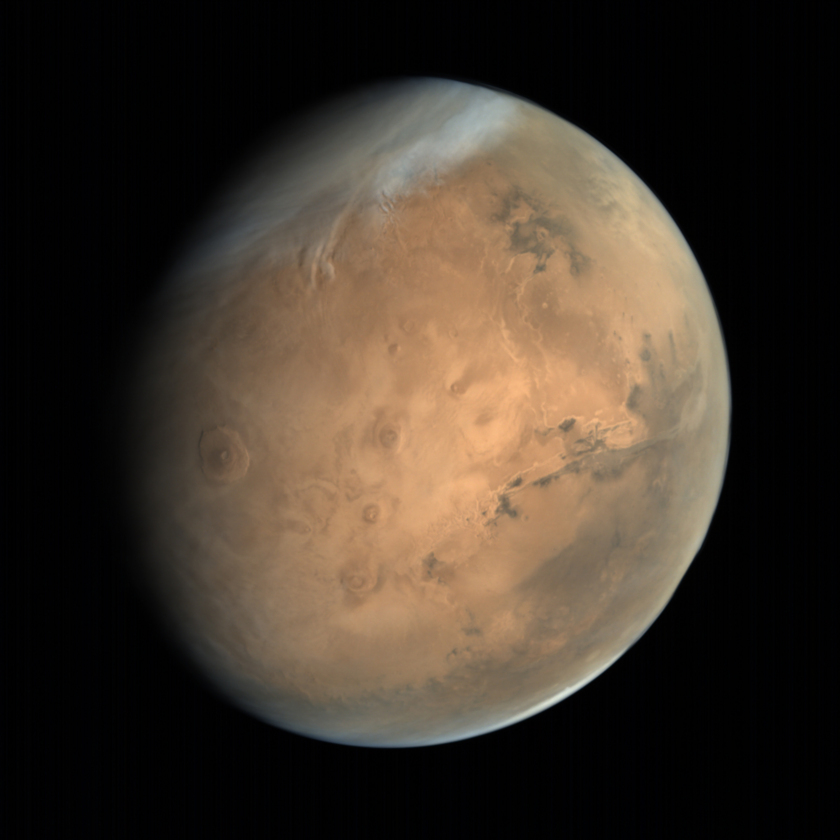

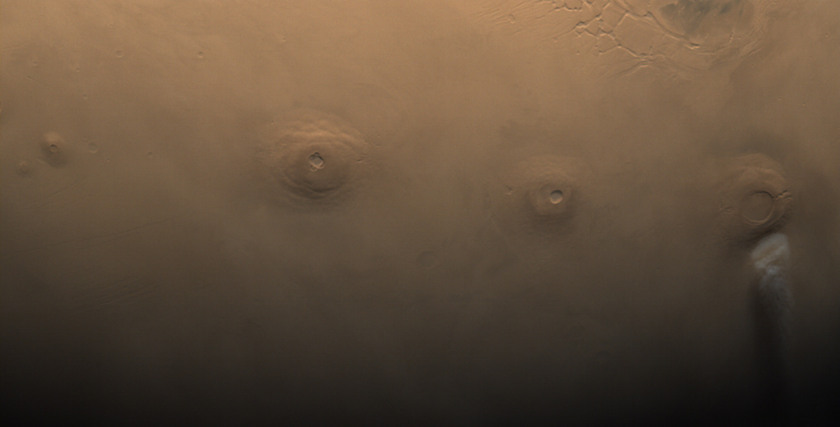

Global view of Mars from MOM: Tharsis Montes and Valles Marineris

Mars Orbiter Mission took this photo on October 4, 2014, from an altitude of 76,680 kilometers.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

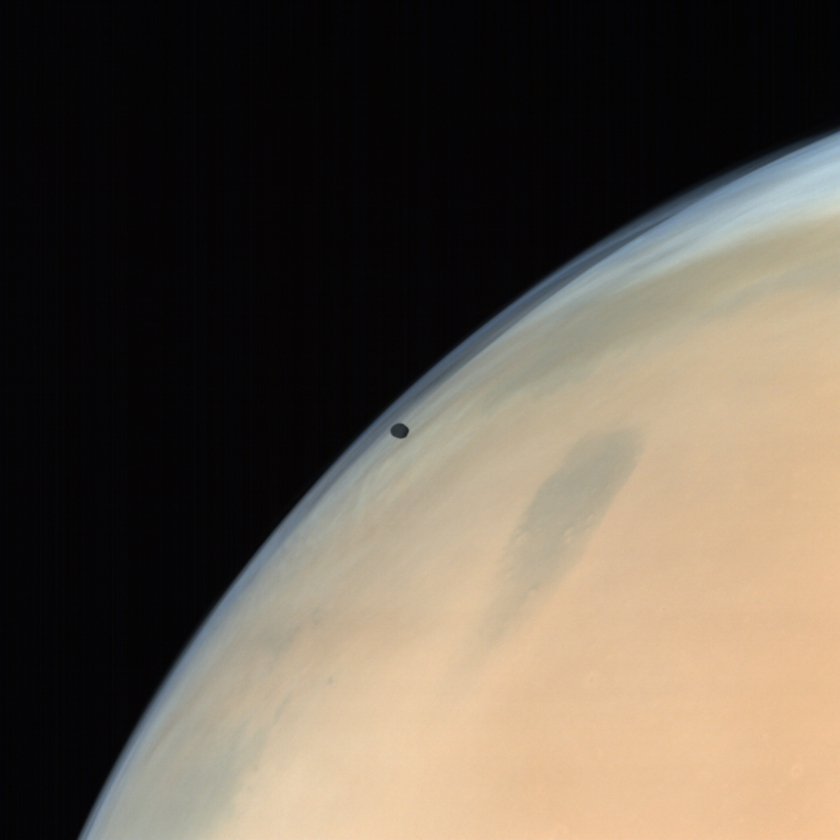

Mars and Phobos

Phobos makes a guest appearance in this nearly global view of Mars taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on October 31, 2014.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Phobos crossing Mars’ disk (animation)

Mars Orbiter Mission took the four photos in this animation, showing Phobos transiting Mars’ disk, over a period of 35 seconds beginning at 3:02:41 on October 7, 2014.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Phobos over Mars from MOM

Mars’ inner moon Phobos appears far darker than the bright clouds of Mars in this view taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on October 14, 2014.

{.img537}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img537}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Phobos over Mars from MOM (detail)

Taken October 14, 2014.

In the data released to date, there’s only one view that I can find of Deimos. It’s one that was released before, but in a weird color; in my processing, I find that it comes out the right color, a brownish gray. It’s a little hard to discern its shape because it is nearly fully lit (that is, the image was taken at a very low phase angle).

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Deimos from Mars Orbiter Mission

Mars Orbiter Mission shot this photo of Mars’ outer moon Deimos on October 14, 2014. The view is onto Deimos’ concave south pole.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

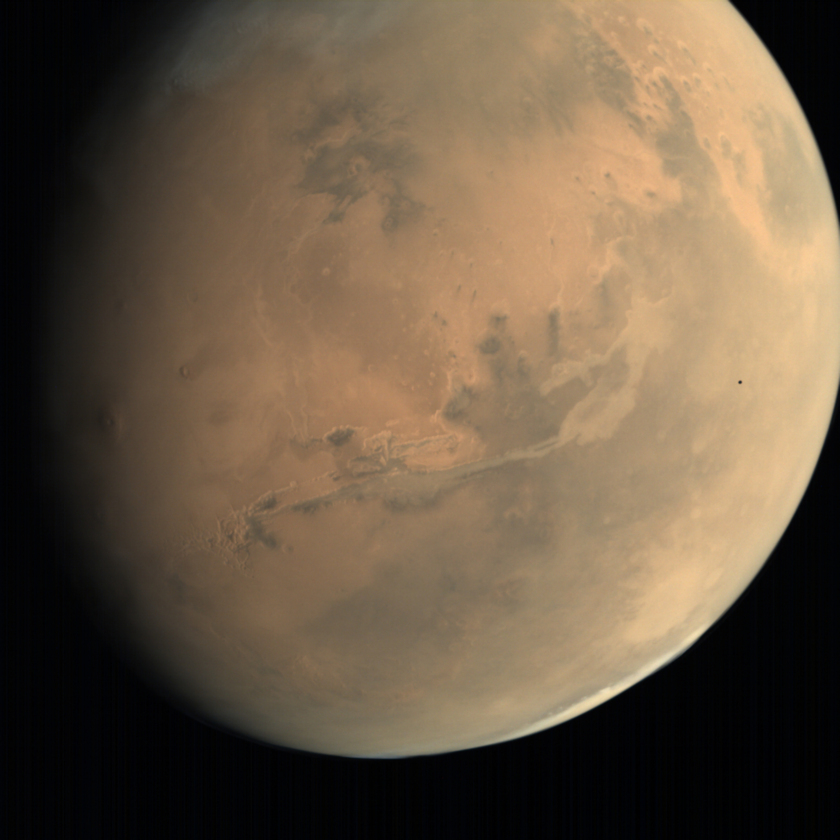

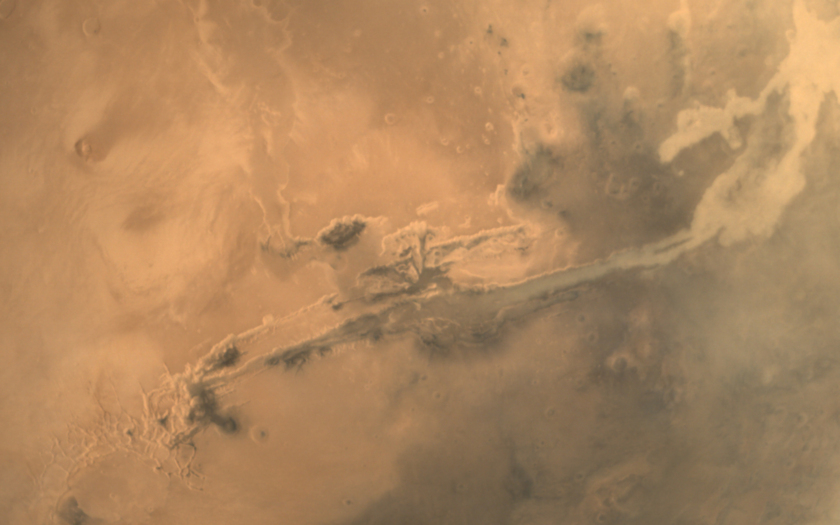

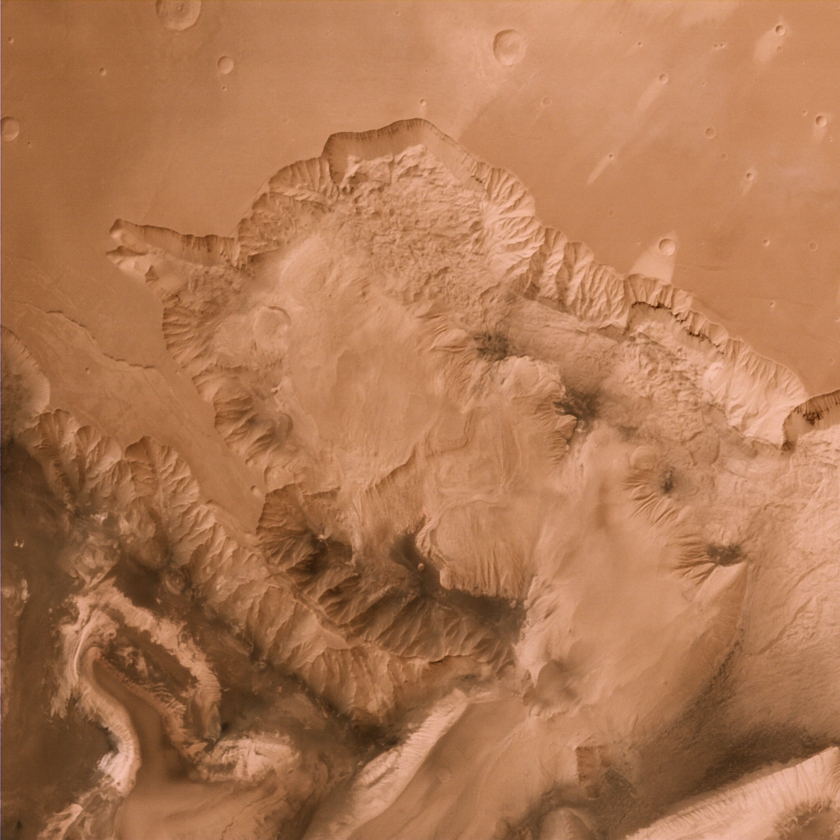

Valles Marineris

Mars Orbiter Mission captured this expansive view of the solar system’s largest canyon on October 20, 2014.

Here’s a view centered on Gale crater, Curiosity’s landing site, showing it in context with some of the steep topography of Mars’ hemispheric dichotomy boundary:

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Gale Crater regional context

Gale Crater – Curiosity’s landing location – is easy to spot in wide-angle views of Mars because of its dark “beard” and the black sand dunes that form outlines around Gale’s central mound. This view was taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on January 17, 2015.

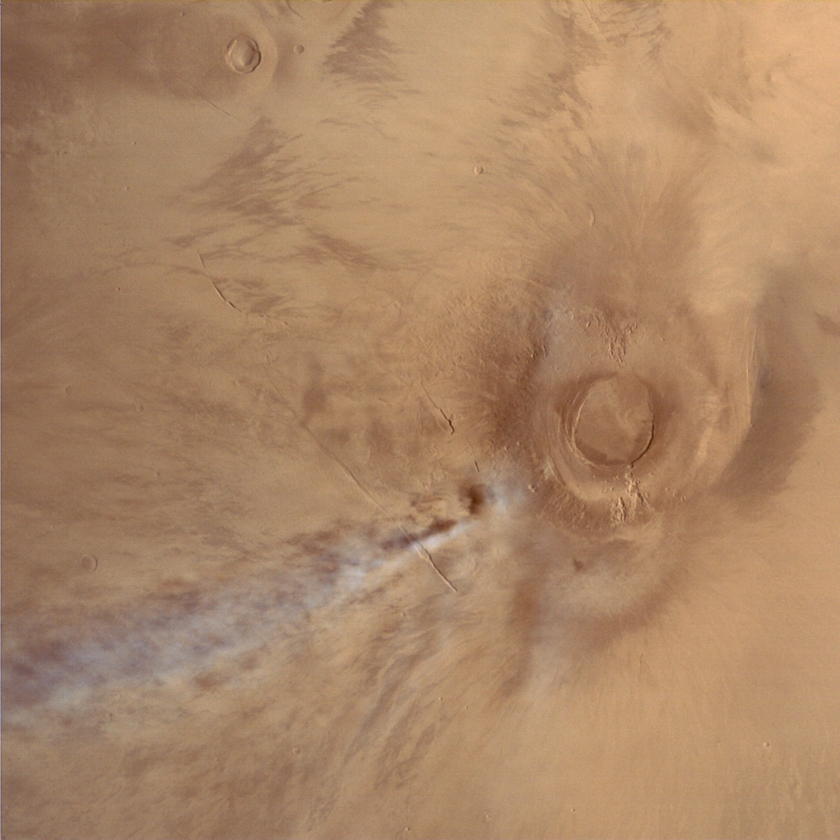

How about a volcano? I always have to look up which of the Tharsis montes is which. The big one in this picture is Arsia, the southernmost. I love the high cloud, and the fact that you can see its shadow cast on the surface.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

Arsia Mons and cloud, Mars

Mars Orbiter Mission took this photo on January 4, 2015, from an altitude of 10,773 kilometers. The image covers an area about 1100 kilometers wide. Arsia is the southernmost of the three Tharsis Montes.

In fact, speaking of the Tharsis Montes, here’s a lovely atmospheric view of all of them (with bonus Uranius and Ceraunius Tholi). I turned it sideways from its original format because I thought it’d make a nice page banner this way.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Emily Lakdawalla

Tharsis Montes

At far left are the small Uranius Tholus and the conical Ceraunius Tholus, close together. Then, from left to right (northeast to southwest) are the three Tharsis Montes: Ascraeus, Pavonis, and Arsia Mons. Arsia has a bit of early morning cloud to the southwest of its peak. The photo was taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on December 13, 2014.

Here’s a much closer view of a bit of Valles Marineris. Pick your favorite chasma and you can find a nice regional view from MOM, I think.

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

Candor and Ophir Chasmata, Mars

Candor Chasma (bottom right) and Ophir Chasma (center), two large canyons in the north-central portion of the Valles Marineris system. Taken by Mars Orbiter Mission on July 19, 2015, from an altitude of 1858 kilometers. The image shows a region about 200 kilometers across.

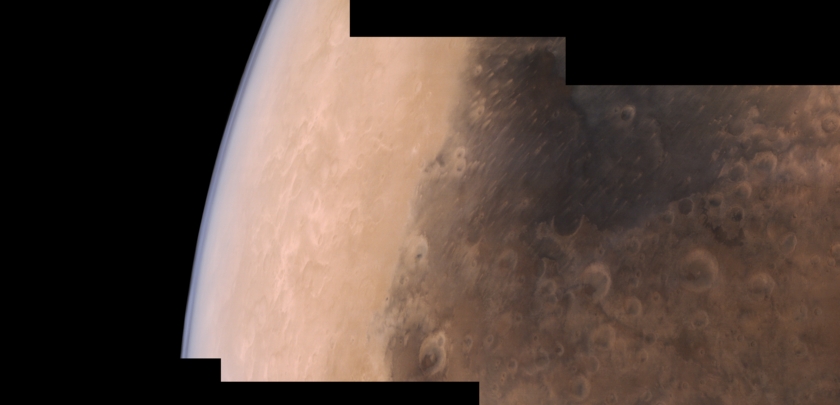

I’ll finish my tour of the data set with this more atmospheric view. Crop it to a rectangle and I think it’d make another terrific page header!

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

{.img840}

ISRO / ISSDC / Justin Cowart

Syrtis Major and the Martian limb from Mars Orbiter Mission

Three frame Mars Orbiter Mission Mars Color Camera mosaic of the Syrtis Major region on September 24, 2015. The first frame was taken while MOM was at an altitude of 7200 km, and the final frame was taken at an altitude of 8300 km 10 minutes later.

Okay. Enough playing around; let’s talk a bit of technical details about the data set.

The official way to access it is through this site. It requires registration for access, but I never received the promised email saying I got access; eventually I got a login to work without it, and was able to get in to get the data. I find that logging in the first time typically does not work; I have to wait for the site to throw an error and then try logging in again. Sometimes I close my browser after a login attempt and then open it again and try logging in again and it tells me I’m already logged in, and then I can access the data through the menus at the top of the page. Whatever works!

Downloading images is time-consuming, because the site limits you to five images at a time (though in practice I never got it to download more than one at a time), and each time you request an image download it takes a minute or two to zip together two versions of the image, one 16-bit and one 32-bit, along with various ancillary data, making for typically 30 Megabytes of downloading for each image.

Fortunately for you, I have downloaded all of the data so you don’t have to, and converted it to various formats.

I am very grateful to announce that Björn Jònsson has updated his wonderful IMG2PNG software to be able to handle Mars Orbiter Mission images.

That allowed me to convert the data from its archival format to one more accessible to the public, PNG.

I collated the ancillary data from the image headers and assembled my own browse page to the data, which you can access here.

For each image you can click a thumbnail to get to a png-formatted version of the image, or download the original PDS-formatted versions, along with detached text labels.

For 42 of the images, there are two versions of the same photo, downlinked through different ground stations, so the data set actually contains 375 unique images.

I highlighted in yellow the ones that are duplicates.

If you would like to download the full data set, I have made several text lists that you can use with wget:

- EDRs

- EDR labels

- EDRs converted to PNG with IMG2PNG

- EDRs converted to PNG with demosaicking

- RDRs converted to PNG

- RDRs - 16-bit

- RDRs - 16-bit image labels

- RDRs - 32-bit

- RDRs - 32-bit image labels

I found that the images all appear orange; the green and blue levels are way too low. By adjusting the levels of a full-globe image so that the south polar clouds are white, I find that assigning an input value of 211 in the green channel and 144 in the blue channel to white makes the color balance look much more like published Hubble photos – and then the same proportion applies to all of the rest of the images in the data set. When I converted the data to PNG, I applied this proportional adjustment to all the images, but the original PDS-formatted images will retain the orange cast.

The RDR images benefit from a little unsharp masking. Reading the documentation for the data set (PDF), I see they used bilinear interpolation to demosaic the images from the raw Bayer filter frames. If you really want to try to get more detail out of the photos, it could be worthwhile to try working with the EDRs, and try some other demosaicking schemes to see if you can get better results. However, the RDRs need flat fielding, and there is no flat field provided with the data set. One useful activity for the community would be to try to devise a flat field.

Most of the images are targeted at Mars, but there are several images taken between 18 and 21 October 2014 that were attempts at targeting Comet Siding Spring. From April to mid-July 2015, there was no imaging due to Mars passing through solar conjunction.

One final, stray observation: This is the first data set I’ve encountered where the ground station that received an image is noted in the image’s filename: D18 and D32 for the Indian Deep Space Network antennas in Bangalore, CNB for Canberra, and GDS for Goldstone. As I mentioned before, some images exist in two versions, each transmitted to a different ground station. The only other archival data set where I’ve seen two versions of single images received through different ground stations is Mariner 10. Most other missions handle this by choosing one or the other to archive, whichever has fewer or no errors, or by creating a product that merges the good parts of two or more error-ridden images to produce the best possible product. In fact, when I downloaded the EDRs, I discovered that the two versions of these images both have missing lines, in different places. Those missing lines do not appear in the RDRs, so ISRO has applied some kind of interpolation to repair flaws in images in the course of converting EDRs to RDRs.

There’s nothing wrong with that if the images are intended only for illustration purposes, but it’s a fairly serious amount of fudging that make the RDRs unsuitable for use as science data, and they should probably make it clearer to users.

Please go forth and process the Mars Orbiter Mission images, and use them in good health! Many thanks to ISRO for designing a camera that takes such unique regional-context images of Mars!

For a complete set of images please refer to the original post on the Planetary Society Blog*